This chapter summarizes the individual administrative tasks you can

perform with the LVM Command Line Interface (CLI) commands to create and

maintain logical volumes.

There are several general features of all LVM CLI commands.

When sizes are required in a command line argument, units can always

be specified explicitly. If you do not specify a unit, then a default is

assumed, usually KB or MB. LVM CLI commands do not accept fractions.

When specifying units in a command line argument, LVM is

case-insensitive; specifying M or m is equivalent, for example, and

powers of 2 (multiples of 1024) are used. However, when specifying the --units

argument in a command, lower-case indicates that units are in multiples

of 1024 while upper-case indicates that units are in multiples of 1000.

Where commands take volume group or logical volume names as

arguments, the full path name is optional. A logical volume called lvol0 in a volume group called vg0 can be specified as vg0/lvol0.

Where a list of volume groups is required but is left empty, a list of

all volume groups will be substituted. Where a list of logical volumes

is required but a volume group is given, a list of all the logical

volumes in that volume group will be substituted. For example, the lvdisplay vg0 command will display all the logical volumes in volume group vg0.

All LVM commands accept a -v argument,

which can be entered multiple times to increase the output verbosity.

For example, the following examples shows the default output of the lvcreate command.

# lvcreate -L 50MB new_vg

Rounding up size to full physical extent 52.00 MB

Logical volume "lvol0" created

The following command shows the output of the lvcreate command with the -v argument.

# lvcreate -v -L 50MB new_vg

Finding volume group "new_vg"

Rounding up size to full physical extent 52.00 MB

Archiving volume group "new_vg" metadata (seqno 4).

Creating logical volume lvol0

Creating volume group backup "/etc/lvm/backup/new_vg" (seqno 5).

Found volume group "new_vg"

Creating new_vg-lvol0

Loading new_vg-lvol0 table

Resuming new_vg-lvol0 (253:2)

Clearing start of logical volume "lvol0"

Creating volume group backup "/etc/lvm/backup/new_vg" (seqno 5).

Logical volume "lvol0" created

You could also have used the -vv, -vvv or the -vvvv argument to display increasingly more details about the command execution. The -vvvv

argument provides the maximum amount of information at this time. The

following example shows only the first few lines of output for the lvcreate command with the -vvvv argument specified.

# lvcreate -vvvv -L 50MB new_vg

#lvmcmdline.c:913 Processing: lvcreate -vvvv -L 50MB new_vg

#lvmcmdline.c:916 O_DIRECT will be used

#config/config.c:864 Setting global/locking_type to 1

#locking/locking.c:138 File-based locking selected.

#config/config.c:841 Setting global/locking_dir to /var/lock/lvm

#activate/activate.c:358 Getting target version for linear

#ioctl/libdm-iface.c:1569 dm version OF [16384]

#ioctl/libdm-iface.c:1569 dm versions OF [16384]

#activate/activate.c:358 Getting target version for striped

#ioctl/libdm-iface.c:1569 dm versions OF [16384]

#config/config.c:864 Setting activation/mirror_region_size to 512

...

You can display help for any of the LVM CLI commands with the --help argument of the command.

commandname --help

To display the man page for a command, execute the man command:

man commandname

The man lvm command provides general online information about LVM.

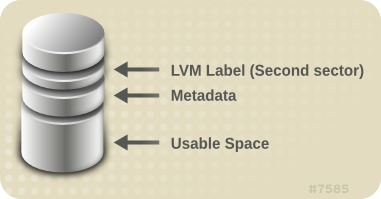

All LVM objects are referenced internally by a UUID, which is

assigned when you create the object. This can be useful in a situation

where you remove a physical volume called

/dev/sdf which is part of a volume group and, when you plug it back in, you find that it is now

/dev/sdk.

LVM will still find the physical volume because it identifies the

physical volume by its UUID and not its device name. For information on

specifying the UUID of a physical volume when creating a physical

volume, see see

Section 6.4, “Recovering Physical Volume Metadata”.

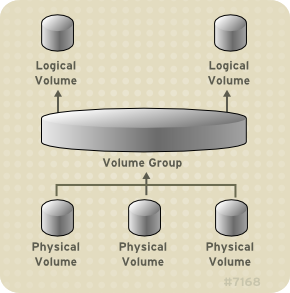

4.3. Volume Group Administration

This section describes the commands that perform the various aspects of volume group administration.

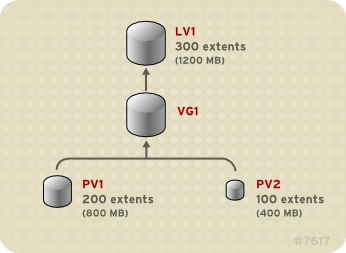

4.3.1. Creating Volume Groups

To create a volume group from one or more physical volumes, use the

vgcreate command. The

vgcreate command creates a new volume group by name and adds at least one physical volume to it.

The following command creates a volume group named vg1 that contains physical volumes /dev/sdd1 and /dev/sde1.

vgcreate vg1 /dev/sdd1 /dev/sde1

When physical volumes are used to create a volume group, its disk

space is divided into 4MB extents, by default. This extent is the

minimum amount by which the logical volume may be increased or decreased

in size. Large numbers of extents will have no impact on I/O

performance of the logical volume.

You can specify the extent size with the -s option to the vgcreate

command if the default extent size is not suitable. You can put limits

on the number of physical or logical volumes the volume group can have

by using the -p and -l arguments of the vgcreate command.

By default, a volume group allocates physical extents according to

common-sense rules such as not placing parallel stripes on the same

physical volume. This is the normal allocation policy. You can use the --alloc argument of the vgcreate command to specify an allocation policy of contiguous, anywhere, or cling.

The contiguous policy requires that new

extents are adjacent to existing extents. If there are sufficient free

extents to satisfy an allocation request but a normal allocation policy would not use them, the anywhere allocation policy will, even if that reduces performance by placing two stripes on the same physical volume. The cling

policy places new extents on the same physical volume as existing

extents in the same stripe of the logical volume. These policies can be

changed using the vgchange command.

In general, allocation policies other than normal are required only in special cases where you need to specify unusual or nonstandard extent allocation.

LVM volume groups and underlying logical volumes are included in the device special file directory tree in the /dev directory with the following layout:

/dev/vg/lv/

For example, if you create two volume groups myvg1 and myvg2, each with three logical volumes named lvo1, lvo2, and lvo3, this create six device special files:

/dev/myvg1/lv01

/dev/myvg1/lv02

/dev/myvg1/lv03

/dev/myvg2/lv01

/dev/myvg2/lv02

/dev/myvg2/lv03

The maximum device size with LVM is 8 Exabytes on 64-bit CPUs.

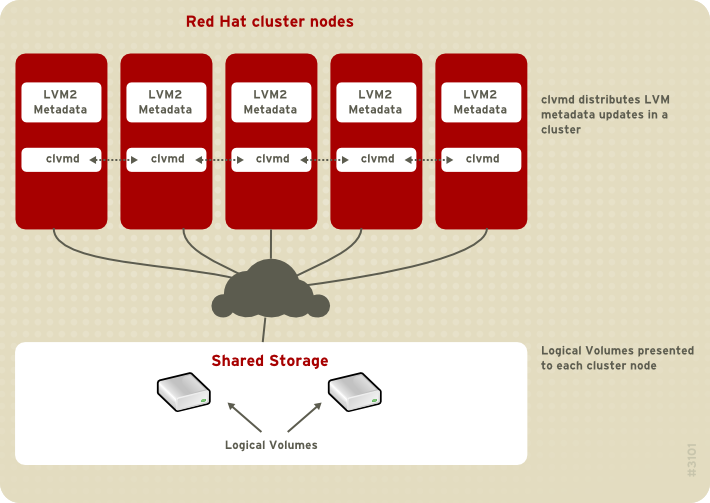

4.3.2. Creating Volume Groups in a Cluster

You create volume groups in a cluster environment with the vgcreate command, just as you create them on a single node.

By default, volume groups created with CLVM on shared storage are

visible to all computers that have access to the shared storage. It is

possible, however, to create volume groups that are local, visible only

to one node in the cluster, by using the -c n of the vgcreate command.

The following command, when executed in a cluster environment,

creates a volume group that is local to the node from which the command

was executed. The command creates a local volume named vg1 that contains physical volumes /dev/sdd1 and /dev/sde1.

vgcreate -c n vg1 /dev/sdd1 /dev/sde1

You can check whether an existing volume group is a clustered volume group with the vgs command, which displays the c attribute if the volume is clustered. The following command displays the attributes of the volume groups VolGroup00 and testvg1. In this example, VolGroup00 is not clustered, while testvg1 is clustered, as indicated by the c attribute under the Attr heading.

[root@doc-07]# vgs

VG #PV #LV #SN Attr VSize VFree

VolGroup00 1 2 0 wz--n- 19.88G 0

testvg1 1 1 0 wz--nc 46.00G 8.00M

4.3.3. Adding Physical Volumes to a Volume Group

To add additional physical volumes to an existing volume group, use the vgextend command. The vgextend command increases a volume group's capacity by adding one or more free physical volumes.

The following command adds the physical volume /dev/sdf1 to the volume group vg1.

vgextend vg1 /dev/sdf1

4.3.4. Displaying Volume Groups

There are two commands you can use to display properties of LVM volume groups: vgs and vgdisplay.

The

vgs command provides volume group information in a configurable form, displaying one line per volume group. The

vgs command provides a great deal of format control, and is useful for scripting. For information on using the

vgs command to customize your output, see

Section 4.8, “Customized Reporting for LVM”.

The vgdisplay command displays volume

group properties (such as size, extents, number of physical volumes,

etc.) in a fixed form. The following example shows the output of a vgdisplay command for the volume group new_vg. If you do not specify a volume group, all existing volume groups are displayed.

# vgdisplay new_vg

--- Volume group ---

VG Name new_vg

System ID

Format lvm2

Metadata Areas 3

Metadata Sequence No 11

VG Access read/write

VG Status resizable

MAX LV 0

Cur LV 1

Open LV 0

Max PV 0

Cur PV 3

Act PV 3

VG Size 51.42 GB

PE Size 4.00 MB

Total PE 13164

Alloc PE / Size 13 / 52.00 MB

Free PE / Size 13151 / 51.37 GB

VG UUID jxQJ0a-ZKk0-OpMO-0118-nlwO-wwqd-fD5D32

4.3.5. Scanning Disks for Volume Groups to Build the Cache File

The vgscan command scans all supported

disk devices in the system looking for LVM physical volumes and volume

groups. This builds the LVM cache in the /etc/lvm/.cache file, which maintains a listing of current LVM devices.

LVM runs the vgscan command automatically at system startup and at other times during LVM operation, such as when you execute a vgcreate command or when LVM detects an inconsistency.

You may need to run the vgscan command

manually when you change your hardware configuration and add or delete a

device from a node, causing new devices to be visible to the system

that were not present at system bootup. This may be necessary, for

example, when you add new disks to the system on a SAN or hotplug a new

disk that has been labeled as a physical volume.

The following example shows the output of a vgscan command.

# vgscan

Reading all physical volumes. This may take a while...

Found volume group "new_vg" using metadata type lvm2

Found volume group "officevg" using metadata type lvm2

4.3.6. Removing Physical Volumes from a Volume Group

To remove unused physical volumes from a volume group, use the vgreduce command. The vgreduce

command shrinks a volume group's capacity by removing one or more empty

physical volumes. This frees those physical volumes to be used in

different volume groups or to be removed from the system.

Before removing a physical volume from a volume group, you can make

sure that the physical volume is not used by any logical volumes by

using the pvdisplay command.

# pvdisplay /dev/hda1

-- Physical volume ---

PV Name /dev/hda1

VG Name myvg

PV Size 1.95 GB / NOT usable 4 MB [LVM: 122 KB]

PV# 1

PV Status available

Allocatable yes (but full)

Cur LV 1

PE Size (KByte) 4096

Total PE 499

Free PE 0

Allocated PE 499

PV UUID Sd44tK-9IRw-SrMC-MOkn-76iP-iftz-OVSen7

If the physical volume is still being used you will have to migrate the data to another physical volume using the pvmove command. Then use the vgreduce command to remove the physical volume:

The following command removes the physical volume /dev/hda1 from the volume group my_volume_group.

# vgreduce my_volume_group /dev/hda1

4.3.7. Changing the Parameters of a Volume Group

The following command changes the maximum number of logical volumes of volume group vg00 to 128.

vgchange -l 128 /dev/vg00

For a description of the volume group parameters you can change with the vgchange command, see the vgchange(8) man page.

4.3.8. Activating and Deactivating Volume Groups

When you create a volume group it is, by default, activated. This

means that the logical volumes in that group are accessible and subject

to change.

There are various circumstances for which you you need to make a

volume group inactive and thus unknown to the kernel. To deactivate or

activate a volume group, use the -a (--available) argument of the vgchange command.

The following example deactivates the volume group my_volume_group.

vgchange -a n my_volume_group

If clustered locking is enabled, add ’e’ to activate or deactivate a

volume group exclusively on one node or ’l’ to activate or/deactivate a

volume group only on the local node. Logical volumes with single-host

snapshots are always activated exclusively because they can only be used

on one node at once.

4.3.9. Removing Volume Groups

To remove a volume group that contains no logical volumes, use the vgremove command.

# vgremove officevg

Volume group "officevg" successfully removed

4.3.10. Splitting a Volume Group

To split the physical volumes of a volume group and create a new volume group, use the vgsplit command.

Logical volumes cannot be split between volume groups. Each existing

logical volume must be entirely on the physical volumes forming either

the old or the new volume group. If necessary, however, you can use the pvmove command to force the split.

The following example splits off the new volume group smallvg from the original volume group bigvg.

# vgsplit bigvg smallvg /dev/ram15

Volume group "smallvg" successfully split from "bigvg"

4.3.11. Combining Volume Groups

Two combine two volume groups into a single volume group, use the vgmerge

command. You can merge an inactive "source" volume with an active or an

inactive "destination" volume if the physical extent sizes of the

volume are equal and the physical and logical volume summaries of both

volume groups fit into the destination volume groups limits.

The following command merges the inactive volume group my_vg into the active or inactive volume group databases giving verbose runtime information.

vgmerge -v databases my_vg

4.3.12. Backing Up Volume Group Metadata

Metadata backups and archives are automatically created on every

volume group and logical volume configuration change unless disabled in

the lvm.conf file. By default, the metadata backup is stored in the /etc/lvm/backup file and the metadata archives are stored in the /etc/lvm/archives file. You can manually back up the metadata to the /etc/lvm/backup file with the vgcfgbackup command.

The vgcfrestore command restores the metadata of a volume group from the archive to all the physical volumes in the volume groups.

4.3.13. Renaming a Volume Group

Use the vgrename command to rename an existing volume group.

Either of the following commands renames the existing volume group vg02 to my_volume_group

vgrename /dev/vg02 /dev/my_volume_group

vgrename vg02 my_volume_group

4.3.14. Moving a Volume Group to Another System

You can move an entire LVM volume group to another system. It is recommended that you use the vgexport and vgimport commands when you do this.

The vgexport command makes an inactive volume group inaccessible to the system, which allows you to detach its physical volumes. The vgimport command makes a volume group accessible to a machine again after the vgexport command has made it inactive.

To move a volume group form one system to another, perform the following steps:

Make sure that no users are accessing files on the active volumes in the volume group, then unmount the logical volumes.

Use the -a n argument of the vgchange command to mark the volume group as inactive, which prevents any further activity on the volume group.

Use the vgexport command to export the volume group. This prevents it from being accessed by the system from which you are removing it.

After you export the volume group, the physical volume will show

up as being in an exported volume group when you execute the pvscan command, as in the following example.

[root@tng3-1]# pvscan

PV /dev/sda1 is in exported VG myvg [17.15 GB / 7.15 GB free]

PV /dev/sdc1 is in exported VG myvg [17.15 GB / 15.15 GB free]

PV /dev/sdd1 is in exported VG myvg [17.15 GB / 15.15 GB free]

...

When the system is next shut down, you can unplug the disks that

constitute the volume group and connect them to the new system.

When the disks are plugged into the new system, use the vgimport command to import the volume group, making it accessible to the new system.

Activate the volume group with the -a y argument of the vgchange command.

Mount the file system to make it available for use.

4.3.15. Recreating a Volume Group Directory

To recreate a volume group directory and logical volume special files, use the vgmknodes command. This command checks the LVM2 special files in the /dev directory that are needed for active logical volumes. It creates any special files that are missing removes unused ones.

You can incorporate the vgmknodes command into the vgscan command by specifying the mknodes argument to the vgscan command.

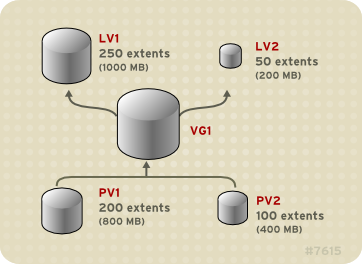

4.4. Logical Volume Administration

This section describes the commands that perform the various aspects of logical volume administration.

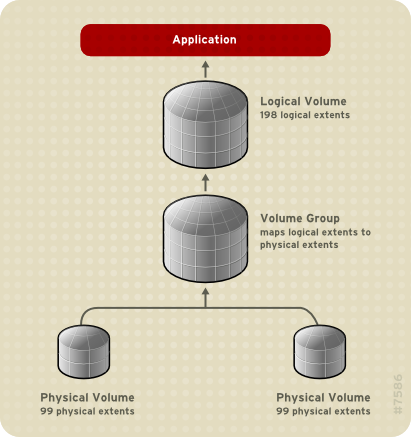

4.4.1. Creating Linear Logical Volumes

To create a logical volume, use the lvcreate command. If you do not specify a name for the logical volume, the default name lvol# is used where # is the internal number of the logical volume.

When you create a logical volume, the logical volume is carved from a

volume group using the free extents on the physical volumes that make

up the volume group. Normally logical volumes use up any space available

on the underlying physical volumes on a next-free basis. Modifying the

logical volume frees and reallocates space in the physical volumes.

The following command creates a logical volume 10 gigabytes in size in the volume group vg1.

lvcreate -L 10G vg1

The following command creates a 1500 megabyte linear logical volume named testlv in the volume group testvg, creating the block device /dev/testvg/testlv.

lvcreate -L1500 -n testlv testvg

The following command creates a 50 gigabyte logical volume named gfslv from the free extents in volume group vg0.

lvcreate -L 50G -n gfslv vg0

You can use the -l argument of the lvcreate

command to specify the size of the logical volume in extents. You can

also use this argument to specify the percentage of the volume group to

use for the logical volume. The following command creates a logical

volume called mylv that uses 60% of the total space in volume group testvol.

lvcreate -l 60%VG -n mylv testvg

You can also use the -l argument of the lvcreate

command to specify the percentage of the remaining free space in a

volume group as the size of the logical volume. The following command

creates a logical volume called yourlv that uses all of the unallocated space in the volume group testvol.

lvcreate -l 100%FREE -n yourlv testvg

You can use -l argument of the lvcreate

command to create a logical volume that uses the entire volume group.

Another way to create a logical volume that uses the entire volume group

is to use the vgdisplay command to find the "Total PE" size and to use those results as input to the lvcreate command.

The following commands create a logical volume called mylv that fills the volume group named testvg.

# vgdisplay testvg | grep "Total PE"

Total PE 10230

# lvcreate -l 10230 testvg -n mylv

The underlying physical volumes used to create a logical volume can

be important if the physical volume needs to be removed, so you may need

to consider this possibility when you create the logical volume. For

information on removing a physical volume from a volume group, see

Section 4.3.6, “Removing Physical Volumes from a Volume Group”.

To create a logical volume to be allocated from a specific physical

volume in the volume group, specify the physical volume or volumes at

the end at the lvcreate command line. The following command creates a logical volume named testlv in volume group testvg allocated from the physical volume /dev/sdg1,

lvcreate -L 1500 -ntestlv testvg /dev/sdg1

You can specify which extents of a physical volume are to be used

for a logical volume. The following example creates a linear logical

volume out of extents 0 through 25 of physical volume /dev/sda1 and extents 50 through 125 of physical volume /dev/sdb1 in volume group testvg.

lvcreate -l 100 -n testlv testvg /dev/sda1:0-25 /dev/sdb1:50-125

The following example creates a linear logical volume out of extents 0 through 25 of physical volume /dev/sda1 and then continues laying out the logical volume at extent 100.

lvcreate -l 100 -n testlv testvg /dev/sda1:0-25:100-

The default policy for how the extents of a logical volume are allocated is

inherit, which applies the same policy as for the volume group. These policies can be changed using the

lvchange command. For information on allocation policies, see

Section 4.3.1, “Creating Volume Groups”.

4.4.2. Creating Striped Volumes

For large sequential reads and writes, creating a striped logical

volume can improve the efficiency of the data I/O. For general

information about striped volumes, see

Section 2.3.2, “Striped Logical Volumes”.

When you create a striped logical volume, you specify the number of stripes with the -i argument of the lvcreate

command. This determines over how many physical volumes the logical

volume will be striped. The number of stripes cannot be greater than the

number of physical volumes in the volume group (unless the --alloc anywhere argument is used).

If the underlying physical devices that make up a striped logical

volume are different sizes, the maximum size of the striped volume is

determined by the smallest underlying device. For example, in a

two-legged stripe, the maximum size is twice the size of the smaller

device. In a three-legged stripe, the maximum size is three times the

size of the smallest device.

The following command creates a striped logical volume across 2

physical volumes with a stripe of 64kB. The logical volume is 50

gigabytes in size, is named gfslv, and is carved out of volume group vg0.

lvcreate -L 50G -i2 -I64 -n gfslv vg0

As with linear volumes, you can specify the extents of the physical

volume that you are using for the stripe. The following command creates a

striped volume 100 extents in size that stripes across two physical

volumes, is named stripelv and is in volume group testvg. The stripe will use sectors 0-50 of /dev/sda1 and sectors 50-100 of /dev/sdb1.

# lvcreate -l 100 -i2 -nstripelv testvg /dev/sda1:0-50 /dev/sdb1:50-100

Using default stripesize 64.00 KB

Logical volume "stripelv" created

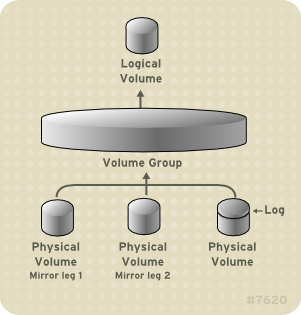

4.4.3. Creating Mirrored Volumes

Creating a mirrored LVM logical volume in a cluster requires the

same commands and procedures as creating a mirrored LVM logical volume

on a single node. However, in order to create a mirrored LVM volume in a

cluster the cluster and cluster mirror infrastructure must be running,

the cluster must be quorate, and the locking type in the

lvm.conf file must be set correctly to enable cluster locking. For an example of creating a mirrored volume in a cluster, see

Section 5.5, “Creating a Mirrored LVM Logical Volume in a Cluster”.

When you create a mirrored volume, you specify the number of copies of the data to make with the -m argument of the lvcreate command. Specifying -m1 creates one mirror, which yields two copies of the file system: a linear logical volume plus one copy. Similarly, specifying -m2 creates two mirrors, yielding three copies of the file system.

The following command creates a mirrored logical volume with a single mirror. The volume is 50 gigabytes in size, is named mirrorlv, and is carved out of volume group vg0:

lvcreate -L 50G -m1 -n mirrorlv vg0

An LVM mirror divides the device being copied into regions that, by default, are 512KB in size. You can use the -R argument of the lvcreate command to specify the region size in MB. You can also change the default region size by editing the mirror_region_size setting in the lvm.conf file.

Due to limitations in the cluster infrastructure, cluster mirrors

greater than 1.5TB cannot be created with the default region size of

512KB. Users that require larger mirrors should increase the region size

from its default to something larger. Failure to increase the region

size will cause LVM creation to hang and may hang other LVM commands as

well.

As a general guideline for specifying the region size for mirrors

that are larger than 1.5TB, you could take your mirror size in terabytes

and round up that number to the next power of 2, using that number as

the -R argument to the lvcreate command. For example, if your mirror size is 1.5TB, you could specify -R 2. If your mirror size is 3TB, you could specify -R 4. For a mirror size of 5TB, you could specify -R 8.

The following command creates a mirrored logical volume with a region size of 2MB:

lvcreate -m1 -L 2T -R 2 -n mirror vol_group

LVM maintains a small log which it uses to keep track of which

regions are in sync with the mirror or mirrors. By default, this log is

kept on disk, which keeps it persistent across reboots and ensures that

the mirror does not need to be re-synced every time a machine reboots or

crashes. You can specify instead that this log be kept in memory with

the --mirrorlog core argument; this

eliminates the need for an extra log device, but it requires that the

entire mirror be resynchronized at every reboot.

The following command creates a mirrored logical volume from the volume group bigvg. The logical volume is named ondiskmirvol and has a single mirror. The volume is 12MB in size and keeps the mirror log in memory.

# lvcreate -L 12MB -m1 --mirrorlog core -n ondiskmirvol bigvg

Logical volume "ondiskmirvol" created

The mirror log is created on a separate device from the devices on

which any of the mirror legs are created. It is possible, however, to

create the mirror log on the same device as one of the mirror legs by

using the --alloc anywhere argument of the vgcreate command. This may degrade performance, but it allows you to create a mirror even if you have only two underlying devices.

The following command creates a mirrored logical volume with a

single mirror for which the mirror log is on the same device as one of

the mirror legs. In this example, the volume group vg0 consists of only two devices. This command creates a 500 megabyte volume named mirrorlv in the vg0 volume group.

lvcreate -L 500M -m1 -n mirrorlv -alloc anywhere vg0

To create a mirror log that is itself mirrored, you can specify the --mirrorlog mirrored argument. The following command creates a mirrored logical volume from the volume group bigvg. The logical volume is named twologvol and has a single mirror. The volume is 12MB in size and the mirror log is mirrored, with each log kept on a separate device.

# lvcreate -L 12MB -m1 --mirrorlog mirrored -n twologvol bigvg

Logical volume "twologvol" created

Just as with a standard mirror log, it is possible to create the

redundant mirror logs on the same device as the mirror legs by using the

--alloc anywhere argument of the vgcreate

command. This may degrade performance, but it allows you to create a

redundant mirror log even if you do not have sufficient underlying

devices for each log to be kept on a separate device than the mirror

legs.

When a mirror is created, the mirror regions are synchronized. For

large mirror components, the sync process may take a long time. When you

are creating a new mirror that does not need to be revived, you can

specify the nosync argument to indicate that an initial synchronization from the first device is not required.

You can specify which devices to use for the mirror legs and log,

and which extents of the devices to use. To force the log onto a

particular disk, specify exactly one extent on the disk on which it will

be placed. LVM does not necessary respect the order in which devices

are listed in the command line. If any physical volumes are listed that

is the only space on which allocation will take place. Any physical

extents included in the list that are already allocated will get

ignored.

The following command creates a mirrored logical volume with a

single mirror and a single log that is not mirrored. The volume is 500

megabytes in size, it is named mirrorlv, and it is carved out of volume group vg0. The first leg of the mirror is on device /dev/sda1, the second leg of the mirror is on device /dev/sdb1, and the mirror log is on /dev/sdc1.

lvcreate -L 500M -m1 -n mirrorlv vg0 /dev/sda1 /dev/sdb1 /dev/sdc1

The following command creates a mirrored logical volume with a

single mirror. The volume is 500 megabytes in size, it is named mirrorlv, and it is carved out of volume group vg0. The first leg of the mirror is on extents 0 through 499 of device /dev/sda1, the second leg of the mirror is on extents 0 through 499 of device /dev/sdb1, and the mirror log starts on extent 0 of device /dev/sdc1. These are 1MB extents. If any of the specified extents have already been allocated, they will be ignored.

lvcreate -L 500M -m1 -n mirrorlv vg0 /dev/sda1:0-499 /dev/sdb1:0-499 /dev/sdc1:0

4.4.3.1. Mirrored Logical Volume Failure Policy

You can define how a mirrored logical volume behaves in the event of a device failure with the mirror_image_fault_policy and mirror_log_fault_policy parameters in the activation section of the lvm.conf file. When these parameters are set to remove, the system attempts to remove the faulty device and run without it. When this parameter is set to allocate,

the system attempts to remove the faulty device and tries to allocate

space on a new device to be a replacement for the failed device; this

policy acts like the remove policy if no suitable device and space can be allocated for the replacement.

By default, the mirror_log_fault_policy parameter is set to allocate.

Using this policy for the log is fast and maintains the ability to

remember the sync state through crashes and reboots. If you set this

policy to remove, when a log device fails

the mirror converts to using an in-memory log and the mirror will not

remember its sync status across crashes and reboots and the entire

mirror will be re-synced.

By default, the mirror_image_fault_policy parameter is set to remove.

With this policy, if a mirror image fails the mirror will convert to a

non-mirrored device if there is only one remaining good copy. Set this

policy to allocate for a mirror device is

slow, as it requires the mirror to resynchronize the devices, but it

will preserve the mirror characteristic of the device.

4.4.3.2. Splitting Off a Redundant Image of a Mirrored Logical Volume

You can split off a redundant image of a mirrored logical volume to

form a new logical volume. To split off an image, you use the --splitmirrors argument of the lvconvert command, specifying the number of of redundant images to split off. You must use the --name argument of the command to specify a name for the newly-split-off logical volume.

The following command splits off a new logical volume named copy from the mirrored logical volume vg/lv. The new logical volume contains two mirror legs. In this example, LVM selects which devices to split off.

lvconvert --splitmirrors 2 --name copy vg/lv

You can specify which devices to split off. The following command splits off a new logical volume named copy from the mirrored logical volume vg/lv. The new logical volume contains two mirror legs consisting of devices /dev/sdc1 and /dev/sde1.

lvconvert --splitmirrors 2 --name copy vg/lv /dev/sd[ce]1

4.4.3.3. Repairing a Mirrored Logical Device

You can use the lvconvert --repair command to repair a mirror after a disk failure. This brings the mirror back into a consistent state. The lvconvert --repair

command is an interactive command that prompts you to indicate whether

you want the system to attempt to replace any failed devices.

To skip the prompts and replace all of the failed devices, specify the -y option on the command line.

To skip the prompts and replace none of the failed devices, specify the -f option on the command line.

To skip the prompts and still indicate different replacement

policies for the mirror image and the mirror log, you can specify the --use-policies argument to use the device replacement policies specified by the mirror_log_fault_policy and mirror_device_fault_policy parameters in the lvm.conf file.

4.4.4. Creating Snapshot Volumes

Use the -s argument of the lvcreate command to create a snapshot volume. A snapshot volume is writeable.

LVM snapshots are not supported across the nodes in a cluster. You

cannot create a snapshot volume in a clustered volume group.

LVM snapshots are not supported for mirrored logical volumes.

The following command creates a snapshot logical volume that is 100 megabytes in size named /dev/vg00/snap. This creates a snapshot of the origin logical volume named /dev/vg00/lvol1.

If the original logical volume contains a file system, you can mount

the snapshot logical volume on an arbitrary directory in order to access

the contents of the file system to run a backup while the original file

system continues to get updated.

lvcreate --size 100M --snapshot --name snap /dev/vg00/lvol1

After you create a snapshot logical volume, specifying the origin volume on the lvdisplay command yields output that includes a a list of all snapshot logical volumes and their status (active or inactive).

The following example shows the status of the logical volume /dev/new_vg/lvol0, for which a snapshot volume /dev/new_vg/newvgsnap has been created.

# lvdisplay /dev/new_vg/lvol0

--- Logical volume ---

LV Name /dev/new_vg/lvol0

VG Name new_vg

LV UUID LBy1Tz-sr23-OjsI-LT03-nHLC-y8XW-EhCl78

LV Write Access read/write

LV snapshot status source of

/dev/new_vg/newvgsnap1 [active]

LV Status available

# open 0

LV Size 52.00 MB

Current LE 13

Segments 1

Allocation inherit

Read ahead sectors 0

Block device 253:2

The lvs command, by default, displays

the origin volume and the current percentage of the snapshot volume

being used for each snapshot volume. The following example shows the

default output for the lvs command for a system that includes the logical volume /dev/new_vg/lvol0, for which a snapshot volume /dev/new_vg/newvgsnap has been created.

# lvs

LV VG Attr LSize Origin Snap% Move Log Copy%

lvol0 new_vg owi-a- 52.00M

newvgsnap1 new_vg swi-a- 8.00M lvol0 0.20

Because the snapshot increases in size as the origin volume

changes, it is important to monitor the percentage of the snapshot

volume regularly with the lvs command to be

sure it does not fill. A snapshot that is 100% full is lost completely,

as a write to unchanged parts of the origin would be unable to succeed

without corrupting the snapshot.

4.4.5. Merging Snapshot Volumes

As of the Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 release, you can use the --merge option of the lvconvert

command to merge a snapshot into its origin volume. If both the origin

and snapshot volume are not open, the merge will start immediately.

Otherwise, the merge will start the first time either the origin or

snapshot are activated and both are closed. Merging a snapshot into an

origin that cannot be closed, for example a root filesystem, is deferred

until the next time the origin volume is activated. When merging

starts, the resulting logical volume will have the origin’s name, minor

number and UUID. While the merge is in progress, reads or writes to the

origin appear as they were directed to the snapshot being merged. When

the merge finishes, the merged snapshot is removed.

The following command merges snapshot volume vg00/lvol1_snap into its origin.

lvconvert --merge vg00/lvol1_snap"

You can specify multiple snapshots on the command line, or you can

use LVM object tags to specify that multiple snapshots be merged to

their respective origins. In the following example, logical volumes vg00/lvol1, vg00/lvol2, and vg00/lvol3 are all tagged with the tag @some_tag". The following command merges the snapshop logical volumes for all three volumes serially: vg00/lvol1, then vg00/lvol2, then vg00/lvol3. If the --background option were used, all snapshot logical volume merges would start in parallel.

lvconvert --merge @some_tag"

For information on tagging LVM objects, see

Appendix C, LVM Object Tags. For further information on the

lvconvert --merge command, see the

lvconvert(8) man page.

4.4.6. Persistent Device Numbers

Major and minor device numbers are allocated dynamically at module

load. Some applications work best if the block device always is

activated with the same device (major and minor) number. You can specify

these with the lvcreate and the lvchange commands by using the following arguments:

--persistent y --major major --minor minor

Use a large minor number to be sure that it hasn't already been allocated to another device dynamically.

If you are exporting a file system using NFS, specifying the fsid parameter in the exports file may avoid the need to set a persistent device number within LVM.

4.4.7. Resizing Logical Volumes

To reduce the size of a logical volume, use the lvreduce

command. If the logical volume contains a file system, be sure to

reduce the file system first (or use the LVM GUI) so that the logical

volume is always at least as large as the file system expects it to be.

The following command reduces the size of logical volume lvol1 in volume group vg00 by 3 logical extents.

lvreduce -l -3 vg00/lvol1

4.4.8. Changing the Parameters of a Logical Volume Group

To change the parameters of a logical volume, use the lvchange command. For a listing of the parameters you can change, see the lvchange(8) man page.

The following command changes the permission on volume lvol1 in volume group vg00 to be read-only.

lvchange -pr vg00/lvol1

4.4.9. Renaming Logical Volumes

To rename an existing logical volume, use the lvrename command.

Either of the following commands renames logical volume lvold in volume group vg02 to lvnew.

lvrename /dev/vg02/lvold /dev/vg02/lvnew

lvrename vg02 lvold lvnew

4.4.10. Removing Logical Volumes

To remove an inactive logical volume, use the lvremove

command. If the logical volume is currently mounted, unmount the volume

before removing it. In addition, in a clustered environment you must

deactivate a logical volume before it can be removed.

The following command removes the logical volume /dev/testvg/testlv from the volume group testvg. Note that in this case the logical volume has not been deactivated.

[root@tng3-1 lvm]# lvremove /dev/testvg/testlv

Do you really want to remove active logical volume "testlv"? [y/n]: y

Logical volume "testlv" successfully removed

You could explicitly deactivate the logical volume before removing it with the lvchange -an command, in which case you would not see the prompt verifying whether you want to remove an active logical volume.

4.4.11. Displaying Logical Volumes

There are three commands you can use to display properties of LVM logical volumes: lvs, lvdisplay, and lvscan.

The

lvs command provides logical volume information in a configurable form, displaying one line per logical volume. The

lvs command provides a great deal of format control, and is useful for scripting. For information on using the

lvs command to customize your output, see

Section 4.8, “Customized Reporting for LVM”.

The lvdisplay command displays logical volume properties (such as size, layout, and mapping) in a fixed format.

The following command shows the attributes of lvol2 in vg00.

If snapshot logical volumes have been created for this original logical

volume, this command shows a list of all snapshot logical volumes and

their status (active or inactive) as well.

lvdisplay -v /dev/vg00/lvol2

The lvscan command scans for all logical volumes in the system and lists them, as in the following example.

# lvscan

ACTIVE '/dev/vg0/gfslv' [1.46 GB] inherit

4.4.12. Growing Logical Volumes

To increase the size of a logical volume, use the lvextend command.

After extending the logical volume, you will need to increase the size of the associated file system to match.

When you extend the logical volume, you can indicate how much you

want to extend the volume, or how large you want it to be after you

extend it.

The following command extends the logical volume /dev/myvg/homevol to 12 gigabytes.

# lvextend -L12G /dev/myvg/homevol

lvextend -- extending logical volume "/dev/myvg/homevol" to 12 GB

lvextend -- doing automatic backup of volume group "myvg"

lvextend -- logical volume "/dev/myvg/homevol" successfully extended

The following command adds another gigabyte to the logical volume /dev/myvg/homevol.

# lvextend -L+1G /dev/myvg/homevol

lvextend -- extending logical volume "/dev/myvg/homevol" to 13 GB

lvextend -- doing automatic backup of volume group "myvg"

lvextend -- logical volume "/dev/myvg/homevol" successfully extended

As with the lvcreate command, you can use the -l argument of the lvextend

command to specify the number of extents by which to increase the size

of the logical volume. You can also use this argument to specify a

percentage of the volume group, or a percentage of the remaining free

space in the volume group. The following command extends the logical

volume called testlv to fill all of the unallocated space in the volume group myvg.

[root@tng3-1 ~]# lvextend -l +100%FREE /dev/myvg/testlv

Extending logical volume testlv to 68.59 GB

Logical volume testlv successfully resized

After you have extended the logical volume it is necessary to increase the file system size to match.

By default, most file system resizing tools will increase the size

of the file system to be the size of the underlying logical volume so

you do not need to worry about specifying the same size for each of the

two commands.

4.4.13. Extending a Striped Volume

In order to increase the size of a striped logical volume, there

must be enough free space on the underlying physical volumes that make

up the volume group to support the stripe. For example, if you have a

two-way stripe that that uses up an entire volume group, adding a single

physical volume to the volume group will not enable you to extend the

stripe. Instead, you must add at least two physical volumes to the

volume group.

For example, consider a volume group vg that consists of two underlying physical volumes, as displayed with the following vgs command.

# vgs

VG #PV #LV #SN Attr VSize VFree

vg 2 0 0 wz--n- 271.31G 271.31G

You can create a stripe using the entire amount of space in the volume group.

# lvcreate -n stripe1 -L 271.31G -i 2 vg

Using default stripesize 64.00 KB

Rounding up size to full physical extent 271.31 GB

Logical volume "stripe1" created

# lvs -a -o +devices

LV VG Attr LSize Origin Snap% Move Log Copy% Devices

stripe1 vg -wi-a- 271.31G /dev/sda1(0),/dev/sdb1(0)

Note that the volume group now has no more free space.

# vgs

VG #PV #LV #SN Attr VSize VFree

vg 2 1 0 wz--n- 271.31G 0

The following command adds another physical volume to the volume group, which then has 135G of additional space.

# vgextend vg /dev/sdc1

Volume group "vg" successfully extended

# vgs

VG #PV #LV #SN Attr VSize VFree

vg 3 1 0 wz--n- 406.97G 135.66G

At this point you cannot extend the striped logical volume to the

full size of the volume group, because two underlying devices are needed

in order to stripe the data.

# lvextend vg/stripe1 -L 406G

Using stripesize of last segment 64.00 KB

Extending logical volume stripe1 to 406.00 GB

Insufficient suitable allocatable extents for logical volume stripe1: 34480

more required

To extend the striped logical volume, add another physical volume

and then extend the logical volume. In this example, having added two

physical volumes to the volume group we can extend the logical volume to

the full size of the volume group.

# vgextend vg /dev/sdd1

Volume group "vg" successfully extended

# vgs

VG #PV #LV #SN Attr VSize VFree

vg 4 1 0 wz--n- 542.62G 271.31G

# lvextend vg/stripe1 -L 542G

Using stripesize of last segment 64.00 KB

Extending logical volume stripe1 to 542.00 GB

Logical volume stripe1 successfully resized

If you do not have enough underlying physical devices to extend the

striped logical volume, it is possible to extend the volume anyway if it

does not matter that the extension is not striped, which may result in

uneven performance. When adding space to the logical volume, the default

operation is to use the same striping parameters of the last segment of

the existing logical volume, but you can override those parameters. The

following example extends the existing striped logical volume to use

the remaining free space after the initial lvextend command fails.

# lvextend vg/stripe1 -L 406G

Using stripesize of last segment 64.00 KB

Extending logical volume stripe1 to 406.00 GB

Insufficient suitable allocatable extents for logical volume stripe1: 34480

more required

# lvextend -i1 -l+100%FREE vg/stripe1

4.4.14. Shrinking Logical Volumes

To reduce the size of a logical volume, first unmount the file system. You can then use the lvreduce command to shrink the volume. After shrinking the volume, remount the file system.

It is important to reduce the size of the file system or whatever

is residing in the volume before shrinking the volume itself, otherwise

you risk losing data.

Shrinking a logical volume frees some of the volume group to be allocated to other logical volumes in the volume group.

The following example reduces the size of logical volume lvol1 in volume group vg00 by 3 logical extents.

lvreduce -l -3 vg00/lvol1

4.5. Controlling LVM Device Scans with Filters

At startup, the vgscan command is run to

scan the block devices on the system looking for LVM labels, to

determine which of them are physical volumes and to read the metadata

and build up a list of volume groups. The names of the physical volumes

are stored in the cache file of each node in the system, /etc/lvm/.cache. Subsequent commands may read that file to avoiding rescanning.

You can control which devices LVM scans by setting up filters in the lvm.conf configuration file. The filters in the lvm.conf file consist of a series of simple regular expressions that get applied to the device names that are in the /dev directory to decide whether to accept or reject each block device found.

The following examples show the use of filters to control which

devices LVM scans. Note that some of these examples do not necessarily

represent best practice, as the regular expressions are matched freely

against the complete pathname. For example, a/loop/ is equivalent to a/.*loop.*/ and would match /dev/solooperation/lvol1.

The following filter adds all discovered devices, which is the

default behavior as there is no filter configured in the configuration

file:

filter = [ "a/.*/" ]

The following filter removes the cdrom device in order to avoid delays if the drive contains no media:

filter = [ "r|/dev/cdrom|" ]

The following filter adds all loop and removes all other block devices:

filter = [ "a/loop.*/", "r/.*/" ]

The following filter adds all loop and IDE and removes all other block devices:

filter =[ "a|loop.*|", "a|/dev/hd.*|", "r|.*|" ]

The following filter adds just partition 8 on the first IDE drive and removes all other block devices:

filter = [ "a|^/dev/hda8$|", "r/.*/" ]

4.8. Customized Reporting for LVM

You can produce concise and customizable reports of LVM objects with the pvs, lvs, and vgs

commands. The reports that these commands generate include one line of

output for each object. Each line contains an ordered list of fields of

properties related to the object. There are five ways to select the

objects to be reported: by physical volume, volume group, logical

volume, physical volume segment, and logical volume segment.

The following sections provide:

A summary of command arguments you can use to control the format of the generated report.

A list of the fields you can select for each LVM object.

A summary of command arguments you can use to sort the generated report.

Instructions for specifying the units of the report output.

This section provides a series of tables that list the information you can display about the LVM objects with the pvs, vgs, and lvs commands.

For convenience, a field name prefix can be dropped if it matches the default for the command. For example, with the pvs command, name means pv_name, but with the vgs command, name is interpreted as vg_name.

Executing the following command is the equivalent of executing pvs -o pv_free.

# pvs -o +free

PFree

17.14G

17.09G

17.14G

Table 4.1, “pvs Display Fields” lists the display arguments of the

pvs command, along with the field name as it appears in the header display and a description of the field.

Table 4.1. pvs Display Fields

|

Argument

|

Header

|

Description

|

|---|

dev_size

|

DevSize

|

The size of the underlying device on which the physical volume was created

|

pe_start

|

1st PE

|

Offset to the start of the first physical extent in the underlying device

|

pv_attr

|

Attr

|

Status of the physical volume: (a)llocatable or e(x)ported.

|

pv_fmt

|

Fmt

|

The metadata format of the physical volume (lvm2 or lvm1)

|

pv_free

|

PFree

|

The free space remaining on the physical volume

|

pv_name

|

PV

|

The physical volume name

|

pv_pe_alloc_count

|

Alloc

|

Number of used physical extents

|

pv_pe_count

|

PE

|

Number of physical extents

|

pvseg_size

|

SSize

|

The segment size of the physical volume

|

pvseg_start

|

Start

|

The starting physical extent of the physical volume segment

|

pv_size

|

PSize

|

The size of the physical volume

|

pv_tags

|

PV Tags

|

LVM tags attached to the physical volume

|

pv_used

|

Used

|

The amount of space currently used on the physical volume

|

pv_uuid

|

PV UUID

|

The UUID of the physical volume

|

The pvs command displays the following fields by default: pv_name, vg_name, pv_fmt, pv_attr, pv_size, pv_free. The display is sorted by pv_name.

# pvs

PV VG Fmt Attr PSize PFree

/dev/sdb1 new_vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.14G

/dev/sdc1 new_vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.09G

/dev/sdd1 new_vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.13G

Using the -v argument with the pvs command adds the following fields to the default display: dev_size, pv_uuid.

# pvs -v

Scanning for physical volume names

PV VG Fmt Attr PSize PFree DevSize PV UUID

/dev/sdb1 new_vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.14G 17.14G onFF2w-1fLC-ughJ-D9eB-M7iv-6XqA-dqGeXY

/dev/sdc1 new_vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.09G 17.14G Joqlch-yWSj-kuEn-IdwM-01S9-XO8M-mcpsVe

/dev/sdd1 new_vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.13G 17.14G yvfvZK-Cf31-j75k-dECm-0RZ3-0dGW-tUqkCS

You can use the --segments argument of the pvs

command to display information about each physical volume segment. A

segment is a group of extents. A segment view can be useful if you want

to see whether your logical volume is fragmented.

The pvs --segments command displays the following fields by default: pv_name, vg_name, pv_fmt, pv_attr, pv_size, pv_free, pvseg_start, pvseg_size. The display is sorted by pv_name and pvseg_size within the physical volume.

# pvs --segments

PV VG Fmt Attr PSize PFree Start SSize

/dev/hda2 VolGroup00 lvm2 a- 37.16G 32.00M 0 1172

/dev/hda2 VolGroup00 lvm2 a- 37.16G 32.00M 1172 16

/dev/hda2 VolGroup00 lvm2 a- 37.16G 32.00M 1188 1

/dev/sda1 vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 16.75G 0 26

/dev/sda1 vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 16.75G 26 24

/dev/sda1 vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 16.75G 50 26

/dev/sda1 vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 16.75G 76 24

/dev/sda1 vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 16.75G 100 26

/dev/sda1 vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 16.75G 126 24

/dev/sda1 vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 16.75G 150 22

/dev/sda1 vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 16.75G 172 4217

/dev/sdb1 vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.14G 0 4389

/dev/sdc1 vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.14G 0 4389

/dev/sdd1 vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.14G 0 4389

/dev/sde1 vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.14G 0 4389

/dev/sdf1 vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.14G 0 4389

/dev/sdg1 vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.14G 0 4389

You can use the pvs -a command to see devices detected by LVM that have not been initialized as LVM physical volumes.

# pvs -a

PV VG Fmt Attr PSize PFree

/dev/VolGroup00/LogVol01 -- 0 0

/dev/new_vg/lvol0 -- 0 0

/dev/ram -- 0 0

/dev/ram0 -- 0 0

/dev/ram2 -- 0 0

/dev/ram3 -- 0 0

/dev/ram4 -- 0 0

/dev/ram5 -- 0 0

/dev/ram6 -- 0 0

/dev/root -- 0 0

/dev/sda -- 0 0

/dev/sdb -- 0 0

/dev/sdb1 new_vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.14G

/dev/sdc -- 0 0

/dev/sdc1 new_vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.09G

/dev/sdd -- 0 0

/dev/sdd1 new_vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.14G

Table 4.2, “vgs Display Fields” lists the display arguments of the

vgs command, along with the field name as it appears in the header display and a description of the field.

Table 4.2. vgs Display Fields

|

Argument

|

Header

|

Description

|

|---|

lv_count

|

#LV

|

The number of logical volumes the volume group contains

|

max_lv

|

MaxLV

|

The maximum number of logical volumes allowed in the volume group (0 if unlimited)

|

max_pv

|

MaxPV

|

The maximum number of physical volumes allowed in the volume group (0 if unlimited)

|

pv_count

|

#PV

|

The number of physical volumes that define the volume group

|

snap_count

|

#SN

|

The number of snapshots the volume group contains

|

vg_attr

|

Attr

|

Status of the volume group: (w)riteable, (r)eadonly, resi(z)eable, e(x)ported, (p)artial and (c)lustered.

|

vg_extent_count

|

#Ext

|

The number of physical extents in the volume group

|

vg_extent_size

|

Ext

|

The size of the physical extents in the volume group

|

vg_fmt

|

Fmt

|

The metadata format of the volume group (lvm2 or lvm1)

|

vg_free

|

VFree

|

Size of the free space remaining in the volume group

|

vg_free_count

|

Free

|

Number of free physical extents in the volume group

|

vg_name

|

VG

|

The volume group name

|

vg_seqno

|

Seq

|

Number representing the revision of the volume group

|

vg_size

|

VSize

|

The size of the volume group

|

vg_sysid

|

SYS ID

|

LVM1 System ID

|

vg_tags

|

VG Tags

|

LVM tags attached to the volume group

|

vg_uuid

|

VG UUID

|

The UUID of the volume group

|

The vgs command displays the following fields by default: vg_name, pv_count, lv_count, snap_count, vg_attr, vg_size, vg_free. The display is sorted by vg_name.

# vgs

VG #PV #LV #SN Attr VSize VFree

new_vg 3 1 1 wz--n- 51.42G 51.36G

Using the -v argument with the vgs command adds the following fields to the default display: vg_extent_size, vg_uuid.

# vgs -v

Finding all volume groups

Finding volume group "new_vg"

VG Attr Ext #PV #LV #SN VSize VFree VG UUID

new_vg wz--n- 4.00M 3 1 1 51.42G 51.36G jxQJ0a-ZKk0-OpMO-0118-nlwO-wwqd-fD5D32

Table 4.3, “lvs Display Fields” lists the display arguments of the

lvs command, along with the field name as it appears in the header display and a description of the field.

Table 4.3. lvs Display Fields

|

Argument

|

Header

|

Description

|

|---|

|

|

Chunk

|

Unit size in a snapshot volume

|

copy_percent

|

Copy%

|

The synchronization percentage of a mirrored logical volume; also used when physical extents are being moved with the pv_move command

|

devices

|

Devices

|

The underlying devices that make up the logical volume: the

physical volumes, logical volumes, and start physical extents and

logical extents

|

lv_attr

|

Attr

|

The status of the logical volume. The logical volume attribute bits are as follows:

| Bit 1: Volume type: (m)irrored, (M)irrored without initial sync, (o)rigin, (p)vmove, (s)napshot, invalid (S)napshot, (v)irtual | | Bit 2: Permissions: (w)riteable, (r)ead-only |

Bit 3: Allocation policy: (c)ontiguous, (n)ormal, (a)nywhere,

(i)nherited. This is capitalized if the volume is currently locked

against allocation changes, for example while executing the pvmove command. | | Bit 4: fixed (m)inor | |

Bit 5: State: (a)ctive, (s)uspended, (I)nvalid snapshot, invalid

(S)uspended snapshot, mapped (d)evice present without tables, mapped

device present with (i)nactive table | | Bit 6: device (o)pen |

|

lv_kernel_major

|

KMaj

|

Actual major device number of the logical volume (-1 if inactive)

|

lv_kernel_minor

|

KMIN

|

Actual minor device number of the logical volume (-1 if inactive)

|

lv_major

|

Maj

|

The persistent major device number of the logical volume (-1 if not specified)

|

lv_minor

|

Min

|

The persistent minor device number of the logical volume (-1 if not specified)

|

lv_name

|

LV

|

The name of the logical volume

|

lv_size

|

LSize

|

The size of the logical volume

|

lv_tags

|

LV Tags

|

LVM tags attached to the logical volume

|

lv_uuid

|

LV UUID

|

The UUID of the logical volume.

|

mirror_log

|

Log

|

Device on which the mirror log resides

|

modules

|

Modules

|

Corresponding kernel device-mapper target necessary to use this logical volume

|

move_pv

|

Move

|

Source physical volume of a temporary logical volume created with the pvmove command

|

origin

|

Origin

|

The origin device of a snapshot volume

|

|

|

Region

|

The unit size of a mirrored logical volume

|

seg_count

|

#Seg

|

The number of segments in the logical volume

|

seg_size

|

SSize

|

The size of the segments in the logical volume

|

seg_start

|

Start

|

Offset of the segment in the logical volume

|

seg_tags

|

Seg Tags

|

LVM tags attached to the segments of the logical volume

|

segtype

|

Type

|

The segment type of a logical volume (for example: mirror, striped, linear)

|

snap_percent

|

Snap%

|

Current percentage of a snapshot volume that is in use

|

stripes

|

#Str

|

Number of stripes or mirrors in a logical volume

|

|

|

Stripe

|

Unit size of the stripe in a striped logical volume

|

The lvs command displays the following fields by default: lv_name, vg_name, lv_attr, lv_size, origin, snap_percent, move_pv, mirror_log, copy_percent. The default display is sorted by vg_name and lv_name within the volume group.

# lvs

LV VG Attr LSize Origin Snap% Move Log Copy%

lvol0 new_vg owi-a- 52.00M

newvgsnap1 new_vg swi-a- 8.00M lvol0 0.20

Using the -v argument with the lvs command adds the following fields to the default display: seg_count, lv_major, lv_minor, lv_kernel_major, lv_kernel_minor, lv_uuid.

# lvs -v

Finding all logical volumes

LV VG #Seg Attr LSize Maj Min KMaj KMin Origin Snap% Move Copy% Log LV UUID

lvol0 new_vg 1 owi-a- 52.00M -1 -1 253 3 LBy1Tz-sr23-OjsI-LT03-nHLC-y8XW-EhCl78

newvgsnap1 new_vg 1 swi-a- 8.00M -1 -1 253 5 lvol0 0.20 1ye1OU-1cIu-o79k-20h2-ZGF0-qCJm-CfbsIx

You can use the --segments argument of the lvs command to display information with default columns that emphasize the segment information. When you use the segments argument, the seg prefix is optional. The lvs --segments command displays the following fields by default: lv_name, vg_name, lv_attr, stripes, segtype, seg_size. The default display is sorted by vg_name, lv_name within the volume group, and seg_start within the logical volume. If the logical volumes were fragmented, the output from this command would show that.

# lvs --segments

LV VG Attr #Str Type SSize

LogVol00 VolGroup00 -wi-ao 1 linear 36.62G

LogVol01 VolGroup00 -wi-ao 1 linear 512.00M

lv vg -wi-a- 1 linear 104.00M

lv vg -wi-a- 1 linear 104.00M

lv vg -wi-a- 1 linear 104.00M

lv vg -wi-a- 1 linear 88.00M

Using the -v argument with the lvs --segments command adds the following fields to the default display: seg_start, stripesize, chunksize.

# lvs -v --segments

Finding all logical volumes

LV VG Attr Start SSize #Str Type Stripe Chunk

lvol0 new_vg owi-a- 0 52.00M 1 linear 0 0

newvgsnap1 new_vg swi-a- 0 8.00M 1 linear 0 8.00K

The following example shows the default output of the lvs command on a system with one logical volume configured, followed by the default output of the lvs command with the segments argument specified.

# lvs

LV VG Attr LSize Origin Snap% Move Log Copy%

lvol0 new_vg -wi-a- 52.00M

# lvs --segments

LV VG Attr #Str Type SSize

lvol0 new_vg -wi-a- 1 linear 52.00M

4.8.3. Sorting LVM Reports

Normally the entire output of the lvs, vgs, or pvs command has to be generated and stored internally before it can be sorted and columns aligned correctly. You can specify the --unbuffered argument to display unsorted output as soon as it is generated.

To specify an alternative ordered list of columns to sort on, use the -O argument of any of the reporting commands. It is not necessary to include these fields within the output itself.

The following example shows the output of the pvs command that displays the physical volume name, size, and free space.

# pvs -o pv_name,pv_size,pv_free

PV PSize PFree

/dev/sdb1 17.14G 17.14G

/dev/sdc1 17.14G 17.09G

/dev/sdd1 17.14G 17.14G

The following example shows the same output, sorted by the free space field.

# pvs -o pv_name,pv_size,pv_free -O pv_free

PV PSize PFree

/dev/sdc1 17.14G 17.09G

/dev/sdd1 17.14G 17.14G

/dev/sdb1 17.14G 17.14G

The following example shows that you do not need to display the field on which you are sorting.

# pvs -o pv_name,pv_size -O pv_free

PV PSize

/dev/sdc1 17.14G

/dev/sdd1 17.14G

/dev/sdb1 17.14G

To display a reverse sort, precede a field you specify after the -O argument with the - character.

# pvs -o pv_name,pv_size,pv_free -O -pv_free

PV PSize PFree

/dev/sdd1 17.14G 17.14G

/dev/sdb1 17.14G 17.14G

/dev/sdc1 17.14G 17.09G

To specify the unit for the LVM report display, use the --units

argument of the report command. You can specify (b)ytes, (k)ilobytes,

(m)egabytes, (g)igabytes, (t)erabytes, (e)xabytes, (p)etabytes, and

(h)uman-readable. The default display is human-readable. You can

override the default by setting the units parameter in the global section of the lvm.conf file.

The following example specifies the output of the pvs command in megabytes rather than the default gigabytes.

# pvs --units m

PV VG Fmt Attr PSize PFree

/dev/sda1 lvm2 -- 17555.40M 17555.40M

/dev/sdb1 new_vg lvm2 a- 17552.00M 17552.00M

/dev/sdc1 new_vg lvm2 a- 17552.00M 17500.00M

/dev/sdd1 new_vg lvm2 a- 17552.00M 17552.00M

By default, units are displayed in powers of 2 (multiples of 1024).

You can specify that units be displayed in multiples of 1000 by

capitalizing the unit specification (B, K, M, G, T, H).

The following command displays the output as a multiple of 1024, the default behavior.

# pvs

PV VG Fmt Attr PSize PFree

/dev/sdb1 new_vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.14G

/dev/sdc1 new_vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.09G

/dev/sdd1 new_vg lvm2 a- 17.14G 17.14G

The following command displays the output as a multiple of 1000.

# pvs --units G

PV VG Fmt Attr PSize PFree

/dev/sdb1 new_vg lvm2 a- 18.40G 18.40G

/dev/sdc1 new_vg lvm2 a- 18.40G 18.35G

/dev/sdd1 new_vg lvm2 a- 18.40G 18.40G

You can also specify (s)ectors (defined as 512 bytes) or custom units.

The following example displays the output of the pvs command as a number of sectors.

# pvs --units s

PV VG Fmt Attr PSize PFree

/dev/sdb1 new_vg lvm2 a- 35946496S 35946496S

/dev/sdc1 new_vg lvm2 a- 35946496S 35840000S

/dev/sdd1 new_vg lvm2 a- 35946496S 35946496S

The following example displays the output of the pvs command in units of 4 megabytes.

# pvs --units 4m

PV VG Fmt Attr PSize PFree

/dev/sdb1 new_vg lvm2 a- 4388.00U 4388.00U

/dev/sdc1 new_vg lvm2 a- 4388.00U 4375.00U

/dev/sdd1 new_vg lvm2 a- 4388.00U 4388.00U